What does imperialism have to do with Vietnam?

French colonialism in Vietnam lasted more than than six decades. By the late 1880s, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were all controlled past France and collectively referred to every bit Indochine Français (French Indochina). Indochina became one of France's most important colonial possessions. French colonialism was focussed largely on production, profit and labour. It had a profound impact on the lives of people in Vietnam.

Justification

To justify their imperialism, the French developed their own principle chosen the mission civilisatrice (or 'civilising mission').

This was, in issue, a French grade of the English 'white human being'southward burden'. Both were theories utilised by powerful European nations to justify their conquest and colonisation of people and places in Africa, Asia and S America.

French imperialists claimed it was their responsibility to colonise undeveloped regions in Africa and Asia, to introduce modern political ideas, social reforms, industrial methods and new technologies. Without European intervention, these places would remain astern, uncivilised and impoverished.

Profit and resources

By and large, the mission civilisatrice was a thin facade. The real motive for French colonialism was profit and economic exploitation.

French imperialism was driven past a demand for resource, raw materials and cheap labour. The development of colonised nations was scarcely considered, except where it happened to benefit French interests.

In full general, French colonialism was more haphazard, expedient and vicious than British colonialism. Paris never designed or promoted a coherent colonial policy in Indochina. So long equally information technology remained in French hands and open to French economic interests, the French government was satisfied.

Colonial government

The political management of Indochina was left to a serial of governors. Paris sent more 20 governors to Indochina between 1900 and 1945. Each had different attitudes and approaches.

French colonial governors, officials and bureaucrats had significant autonomy and authority, so often wielded more power than they should have or was necessary. This encouraged cocky-interest, abuse, venality and heavy-handedness.

The Nguyen emperors remained every bit figurehead monarchs in Vietnam but from the late 1800s, they exercised niggling political ability.

'Divide and dominion'

To minimise local resistance, the French employed a 'separate and rule' strategy, undermining Vietnamese unity by playing local mandarins, communities and religious groups against each other.

The nation was carved into three separate pays (provinces): Tonkin in the north, Annam along the fundamental declension and Cochinchina in the due south. Each of these pays was administered separately.

Under French colonial rule, there was no national identity or authority in Vietnam or its neighbours. According to ane French colonial edict, it was fifty-fifty illegal to use the name 'Vietnam'.

Economic transformation

Turn a profit, not politics, was the driving forcefulness behind French colonisation. Over time, colonial officials and French companies transformed Vietnam'due south thriving subsistence economy into a proto-capitalist system, based on land ownership, increased production, exports and low wages.

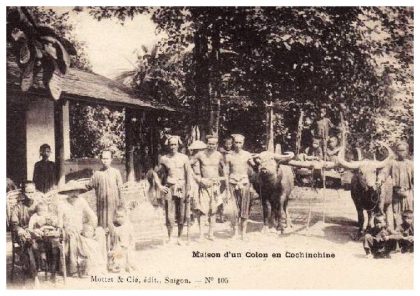

Millions of Vietnamese no longer worked to provide for themselves; they now worked for the benefit of French colons (settlers). The French seized vast swathes of land and reorganised them into large plantations. Pocket-size landholders were given the option of remaining as labourers on these plantations or relocating elsewhere.

Where in that location were labour shortfalls, Viet farmers were recruited en masse from outlying villages. Sometimes they came voluntarily, lured by false promises of high wages; sometimes they were conscripted at the point of a gun.

Rice and safe

Rice and rubber were the main cash crops of these plantations. The amount of land used for growing rice nearly quadrupled in the 20 years after 1880 while Cochinchina (southern Vietnam) had 25 gigantic condom plantations.

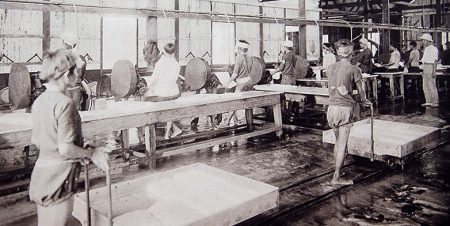

By the 1930s, Indochina was supplying 60,000 tons of safety each year, five per cent of all global production. The French likewise constructed factories and built mines to tap into Vietnam'due south deposits of coal, tin can and zinc.

Most of this cloth was sold abroad equally exports. Most of the profits lined the pockets of French capitalists, investors and officials.

Life under colonialism

The workers on plantations in French Indochina were known as 'coolies', a derogatory term for Asian labourers. They worked long hours in debilitating conditions for wages that were pitifully small. Some were paid in rice rather than money.

The working day could be every bit long as 15 hours, without breaks or acceptable nutrient and freshwater. French colonial laws prohibited corporal punishment only many officials and overseers used it anyway, chirapsia wearisome or reluctant workers.

Malnutrition, dysentery and malaria were rife on plantations, especially those producing prophylactic. It was not uncommon for plantations to have several workers die in a unmarried day.

Atmospheric condition were specially poor on the plantations owned by French tyre manufacturer Michelin. In the 20 years between the two earth wars, one Michelin-owned plantation recorded 17,000 deaths. Vietnamese peasant farmers who remained outside the plantations were bailiwick to the corvee, or unpaid labour. Introduced in 1901, the corvee required male person peasants of adult age to complete 30 days of unpaid work on government buildings, roads, dams and other infrastructure.

Colonial taxes and opium

The French also burdened the Vietnamese with an extensive taxation system. This included income tax on wages, a poll tax on all developed males, stamp duties on a wide range of publications and documents, and imposts on the weighing and measuring of agricultural goods.

Fifty-fifty more lucrative were the state monopolies on rice wine and salt – commodities used extensively past locals. Near Vietnamese had previously made their own rice wine and gathered their own common salt – but past the offset of the 1900s, both could but exist purchased through French outlets at heavily inflated prices.

French officials and colonists likewise benefited from growing, selling and exporting opium, a narcotic drug extracted from poppies. State was set aside to abound opium poppies and past the 1930s, Vietnam was producing more fourscore tonnes of opium each twelvemonth. Not only were local sales of opium very profitable, its addictiveness and stupefying furnishings were a useful class of social control.

By 1935, France's collective sales of rice wine, salt and opium were earning more 600 meg francs per annum, the equivalent of $US5 billion today.

Local collaborators

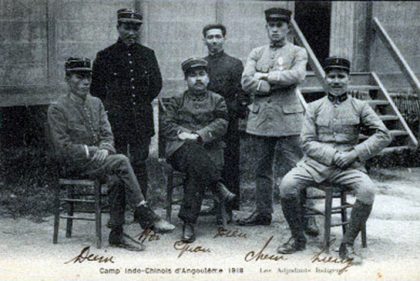

Harnessing and transforming Vietnam's economic system required considerable local back up. France never had a big military presence in Indochina (there were simply 11,000 French troops there in 1900) nor were there plenty Frenchmen to personally manage this transformation. Instead, the French relied on a small number of local officials and bureaucrats.

Called nguoi phan quoc ('traitor') by other locals, these Vietnamese supported colonial rule by collaborating with the French. They often held positions of authority in local regime, businesses or economical institutions, like the Banque de fifty'Indochine (the French Bank of Indochina). They did this for reasons of cocky-involvement or because they held Francophile (pro-French) views.

French propagandists held these collaborators up equally an example of the mission civilisatrice benefiting the Vietnamese people. Some collaborators were given scholarships to report in French republic; a few even received French citizenship. Possibly the most famous collaborator was Bao Dai, the last of the Nguyen emperors (reigned 1926-45). Bao Dai was educated at Paris' Lycee Condorcet and became a lifelong Francophile.

Benefits

French colonialism did provide some benefits for Vietnamese order, most noticeable of which were improvements in education.

French missionaries, officials and their families opened main schools and provided lessons in both French and Viet languages. The University of Hanoi was opened by colonists in 1902 and became an important national centre of learning. A quota of Viet students was given scholarships to study in France.

These changes, however, were really merely significant in the cities: at that place was little or no try to educate the children of peasant farmers. The syllabuses at these schools reinforced colonial control by stressing the supremacy of French values and civilisation.

Cultural impact

Colonialism as well produced a physical transformation in Vietnamese cities. Traditional local temples, pagodas, monuments and buildings, some of which had stood for a millennium, were declared derelict and destroyed. Buildings of French architecture and manner were erected in their place.

The Vietnamese names of cities, towns and streets were changed to French names. Significant business, such equally banking and mercantile trade, was conducted in French rather than local languages.

If not for the climate and people, some parts of Hanoi and Saigon could have been mistaken for parts of Paris, rather than a south-eastward Asian majuscule.

A historian's view:

"The French 'civilising mission' was the transformation of subject peoples into loyal French men and women. Through education and examinations, it was theoretically possible for a Vietnamese to obtain French citizenship, with all its privileges. Yet in reality, the criteria for citizenship were manipulated to ensure that field of study citizens never threatened French political power."

Melvin E. Folio

1. The French colonisation of Vietnam began in earnest in the 1880s and lasted vi decades. The French justified their imperialism with a 'civilising mission', a pledge to develop backward nations.

ii. In reality, French colonialism was importantly driven by economic interests. French colonists were interested in acquiring state, exploiting labour, exporting resources and making profit.

three. Vietnamese land was seized by the French and collectivised into large rice and prophylactic plantations. Local farmers were forced to labour on these plantations in difficult and dangerous conditions.

iv. The French as well imposed a range of taxes on the local population and implemented monopolies on critical goods, such every bit opium, salt and alcohol.

5. French colonisers were relatively few in number so were assisted by Francophile collaborators among the Vietnamese people. These collaborators assisted in the assistants and exploitation of French Indochina.

Citation information

Title: "French colonisation in Vietnam"

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/french-colonisation-in-vietnam/

Appointment published: January seven, 2019

Date accessed: March 25, 2022

Copyright: The content on this folio may not be republished without our limited permission. For more than data on usage, delight refer to our Terms of Use.

Source: https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/french-colonialism-in-vietnam/

Enregistrer un commentaire for "What does imperialism have to do with Vietnam?"